“Conjure” is a collaboration with Professor Hiroshi Ishii's Tangible Media Group, what started as a class project has turned into an ongoing design exploration, re-thinking methods of access to rapidly-changing digital information.. Our team includes Dan Levine, Kalli Retzepi, and Jesper Alkestup. Our prototypes, developed in concert with blind participants, demonstrate a proof-of-concept for a new realm of information display, most recently leading to a CHI2019 paper submission.

Premise

Assistive technologies are siloed within their own paradigm and treated as irrelevant to significant advancements in graphic design. We started with the premise that techniques, organizational advantages, and forms from modern graphical interfaces can be translated into physical, tangible interfaces, which are accessible to blind individuals. Rather than bypassing these visual elements, our prototypes explore methods for rendering them to a dynamic shape display.

Background

Text-based

Traditional screen reading technology and interaction techniques provides access to mostly static and text-based elements. For dynamic elements, screen readers are limited to reading the changing states of more complex user interfaces. However, dynamic interface accessibility remains a challenge to current screen-readers because of the difficulty of displaying important, real-time, content changes through a serial audio interface without distracting or overloading the user.

Non-text based

For non-textual information such as images, screen-reader assistive technologies rely on descriptions of inaccessible visual-only media. HTML and other formats include alt-text (alternative text), a descriptive text tied to media objects to be spoken aloud by screen-readers. The alt-text method is very limited, giving the user a short, sentence or two description of the key aspects of a media object. In the case of complex and dynamic graphics such as graphs, animations, and videos alt-text is likely insufficient. In the case of a video, an audio description (AD) adds an audio-visual track to video. This pre-recorded audio track is a description of important information that is not communicated through the existing ambient audio or dialogue. However, like alt-text, AD requires post hoc content authors, lacks spatial information, and does not invite the user to explore and interpret media independently.

Prototyping

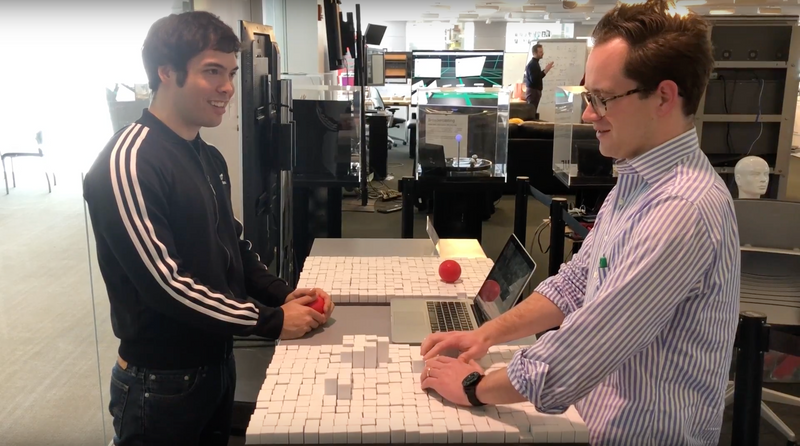

In order to test a variety of dynamic translations of visual media into physical forms, we created a websockets-based pipeline that enables communication to shape displays. The shape-changing platform, created by the Tangible Media Group, is comprised of three dynamic shape displays that move pins vertically in real-time. The hardware uses custom Arduino boards that run a PID controller to sense and move the positions of the pins through motorized slide potentiometers.

This pipeline communicates matrices as pin heights regardless of the language used to prototype our application designs. It uses an Elixir Phoenix websockets protocol residing on a cloud-based server. The server acts as a middleman between the OpenFrameworks-based shape displays and all other sensor or computer inputs.

Case study: Video chat

Two thirds of the information, feeling, and meaning in human interaction come from non-verbal cues, many of which originate from the face. Hence, lack of visual non-verbal cues can lead to social disconnect and isolation for people who are blind or visually impaired. This particular design exploration assisted human-to-human interaction for the blind by mediating affective communication of facial expressions. The interface leverages tangible and spatial qualities of shape displays to deliver dynamic facial movements encountered in our physical or virtual environment, allowing them to be explored and interpreted by touch.

Process

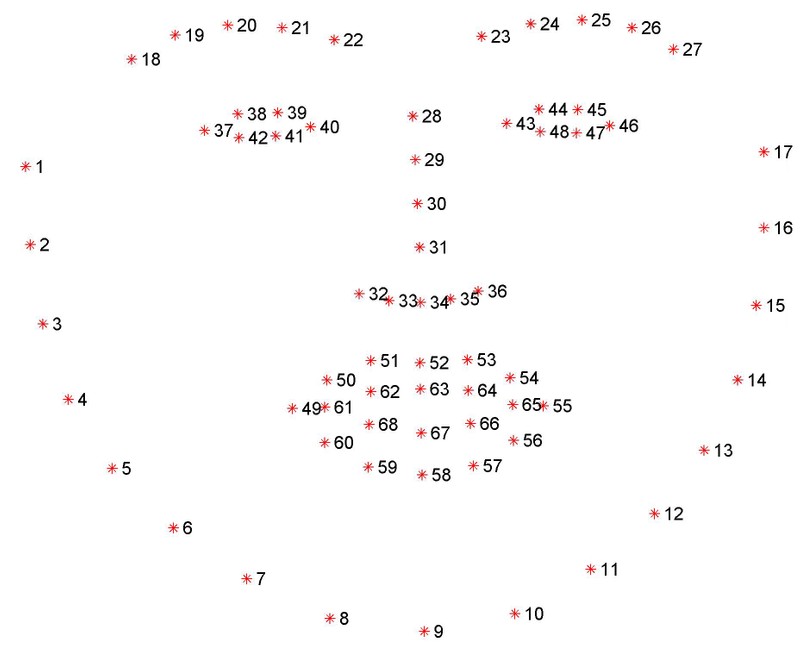

I created an image processing algorithm in Python that uses Haar cascade classifiers trained to detect faces. Using dlib's Histogram of Oriented Gradients (HOG) combined with a linear classifier I am able to track 68 facial landmarks in a real time video stream. With OpenCV, I used found landmarks to draw a face from vectors of various weights, representing facial features. This rapidly-updating matrix is then sent to the shape display over websockets, see more in the code repo.

During preliminary experience testing with three blind users we found that facial features are distinguishable and participants were able to make real-time interpretations while carrying a conversation. When users compared their experience to affective computing systems, all three preferred our application citing their independence to learn and develop their own judgments.

What I learned

An early prototype allowed the face to move position across the matrix in response to head movements. This particular design performed poorly during our informal testing. Blind users found difficulty targeting and re-targeting facial features as they were forced to continuously re-orient to the speaker’s head position. This feedback lead us to a design iteration that implements transformations in OpenCV to keep the displayed face centered within the matrix and at a consistent scale. Re-tests found that designing for ease of orientation and targeting improved both distinguishing unique facial features and making real-time affective interpretations.

Case study: 2D games

Visually impaired and blind people are increasingly getting left behind in the age of screen based interfaces. With this case study, we explored how tangible games can help by facilitating dynamic and physical interactions. Kids are increasingly learning from instructional videos and educational games, but these interactions rely heavily on graphical user-interfaces. Consequently, an already under-served segment (of blind users) cannot participate on equal terms, which broadens the educational gap between visually impaired and blind people relative to sighted people.

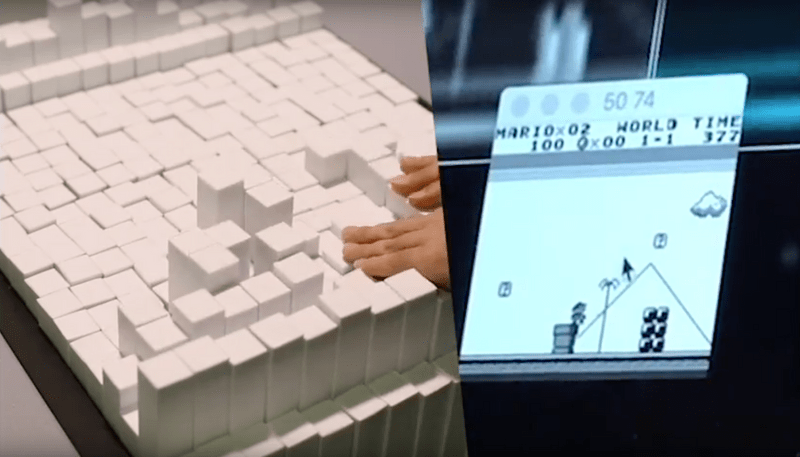

We drew insights from our face studies, and found parallel qualities in a number of popular two-dimensional games. This likeness enabled a relatively simple translation of games into a dynamic physical medium. Here, we chose Nintendo’s Super Mario Land because it exhibits an ego-centric configuration - the player resides in the center of the screen and the world moves around the player. Like the face transformations, this design enables users to easily re-target and orient to a physical landscape.

Process

Based on our previous observations, our approach to this problem was twofold: 1) develop a method for translating existing games into a physical medium, and 2) create an interactive mechanism that does not distract from tangible information gathering. To translate existing games, we extended PyBoy, an open source Python-based Gameboy emulator. We used the Pillow library for various image processing on each frame's pixels to create a matrix of pin heights, which we then sent to the shape display via web-sockets, see our branch.

Blind players noted they could understand and maintain the location of the main character with relative ease. They could pick out features from the environment, like holes in the ground, clouds in the sky, and elevated surfaces. They were also able to successfully interact with adversaries in the game by differentiating moving adversaries with sound cues while tracking them by touch to execute a coordinated take down of the adversary!

What I learned

Our first iteration of interaction design used a voice interface to control Mario. Players would say "jump" and Mario would jump. This design was driven by a desire NOT to interrupt the user's tangible exploration of the environment. However, the voice commands added cognitive load because of the removed experience of using your voice to move your avatar's body. Thus, we re-thought the player’s experience and control of the avatar.

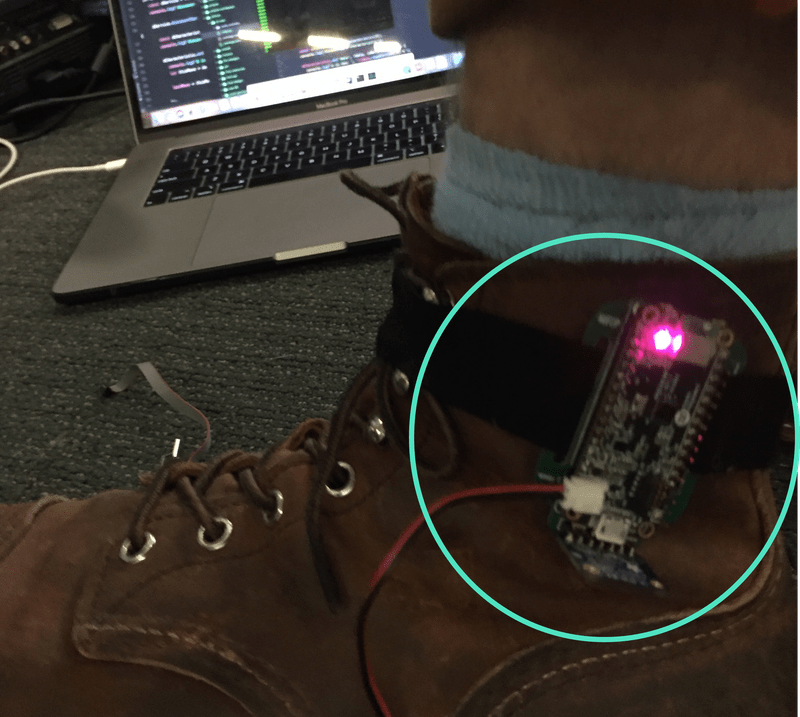

In the next phase, we designed a wearable controller that created congruency between the user's interaction and the tangible display.

The sensor used lidar to measures distances from the wearer's ankle to the ground by detecting reflected laser pulses. We classified wearer movements as walking or jumping by calculating velocity and peaks. I created a simple Node.js app that listened to bluetooth messages from the sensors. The app then controlled the game's Avatar movements and game-play sounds through our existing websockets-based pipeline.

This second iteration of the interaction design was well-received by testers. With little instruction, users intuitively controlled Mario while concurrently feeling the scene to gather real-time information about the landscape and interacting with obstacles and adversaries.